Bricksscience.com is part of the brickwahl.com universe that also includes brickspicks.com (music and culture), bricksbrain.com (cognition, perception and my epilepsy), brickspolitics.com and brickshistory.com.

Gifting

Like so many hundreds if not thousands of English nouns, gift actually began as a verb but at some point a millennium ago was nouned only to be reverbed in the last century and now sits uncomfortably as both noun and verb. My guess it’ll be mostly a verb in a generation or two, since present, itself a nouned verb, has pretty much the same meaning as gift, and has the advantage of being bisyllabic, so the noun can have a different syllable stress than the verb, which to the ear makes them two completely separate words though the eye will wonder occasionally why they’re spelled the same.

English has the ability to render almost any noun into a verb simply through context—putting it in the sentence where a verb should be, and then adding whatever suffixes are required—gifting, gifted, gifts—by regular verb conjugation. And English can also turn verbs into nouns simply by dropping the conjugation and putting it in a sentence where a noun should be. Usually it’s just a temporary or even a one time only transformation, but then sometimes they stick. Gifting has stuck. But then so have many, perhaps even most English verbs. A lot of verbs in English would not be verbs at all if someone hadn’t had the urge to use it as a verb because there was no other way of expressing what one was actually doing with the noun. So you verbed the noun. Easy enough. Thus someone a thousand years ago, perhaps a Norman who didn’t know his Old English verbs anyway, used the correct English verb giften as a noun. Soon everyone was. And look what trouble it’s caused now.

A quick look through the dictionary (if you’re so inclined or bored enough to actually read a dictionary) will reveal an incredibly high proportion of our nouns have been verbs at some point and vice versa. Most languages can’t actually do so, their grammar rules are far too complex. But the language gods have gifted us with the ability to wantonly noun and verb our little brains out, and worse yet, be understood. All we can do is watch meanings shift right before our eyes. Or ears. Whatever.

Big bacterium

A bacterium (I’ve always wanted to say a bacterium) of the largest known bacteria is nearly an inch long. Whatever the bacteriological word for gnarly is, this is that. Not only can you see them with the naked eye, but you can see them with the naked eye in the naked everything, if that’s your thing. But I digress. Anyway, they make great pets.

That 100,000 years before recorded history

For most of that 100K years human history was pretty much just the happenings of very small bands of people just doing hunter gatherer things. What seem like momentous occurrences to us—the peopling of the Western Hemisphere, for instance—happened over thousands of years and hundreds of generations. About twenty thousand years ago settlements got a little larger in places, architecture began, and trade networks appeared. But even then it was all small and incremental. Happening large enough to rate as history didn’t begin until ten thousand years ago or so, and even then it took awhile before cities, government, law, large scale economics and the technologies that enabled them, exponentially growing populations, epidemic disease, war, organized religion and writing, all new things, began to develop to the point that enabled things to happen on such a scale that they can be considered historical and not just the goings on a few dozen or few hundred people in family groups. History, that is involving actual events and actual people does not extend much past the 5000 years of recorded history, as you need writing to record history. What happened before then is a sort of human deep time, that is the the first two to three hundred thousand years the Homo sapiens were on the planet, and the two million years of archaic humans immediately prior to us. This Deep Time isn’t likely to go on much further, though, certainly not millions of years, as Homo sapiens appear to be the evolutionary dead end of eight or so million years of bipedal ape evolution. We’re all that’s left of all those other species, and all species eventually go extinct, mammals a little faster, primates maybe faster still. Species of bipedal apes seem to have a fairly brief shelf life (Neanderthals, for instance, probably lasted four hundred thousand years.) It’s weird to think of humans being with pronghorns, horseshoe crabs and tuataras, but each of us critters is the very last in our lines of evolution, and when the last pronghorn, horseshoe crab, tuatara or human dies, an entire long line of evolution dies with it. What an epic work of human history that will make. Too bad there’ll be no one around to read it.

Radiodonts

The last radiodonts disappeared in the Devonian, 400 million years ago. Yet some of them (found in sedimentary rocks in China and British Columbia) were fossilized so perfectly that their anatomy can be studied in exquisite detail. Hence this gorgeous diagram. Fabulously weird critters, the radiodonts. They came about as part of what is called the Cambrian Explosion of life forms, beginning 538.8 million years ago (I love the “.8”, they can’t narrow it down to a specific day of the week?) and lasted for I think 13 to as many as 25 million years in a time during which evolution went nuts in a world never really evolved in so dramatically before. Thirteen to twenty five million years actually sounds like an enormous slab of time, but we’re talking deep time here, where thirteen to twenty five million years is just a smallish slab of Earth’s geologic history. Just an hour’s worth of geologic time. Our ancestors began then, too, pathetic little things with a proto notocord, which evolved into spinal columns which is what makes vertebrates vertebrate. Thus you and revolting looking jawless lampreys are actually related, I mean if you retrace your family tree back nearly half a billion years, which I don’t, personally. I stop at Bigfoot.

A moment in Deep Time

This shot from the Irish coast appears in my feed regularly, invariably captioned as 350 million years of geologic history. Actually it’s about a hundred thousand or so years of sedimentation laid down 350 million years ago, basically a snapshot of a long ago geologic moment in Deep Time. Which is pretty cool, actually, but apparently more difficult to conceptualize, though why I don’t know.

Hummingbirdasaurus

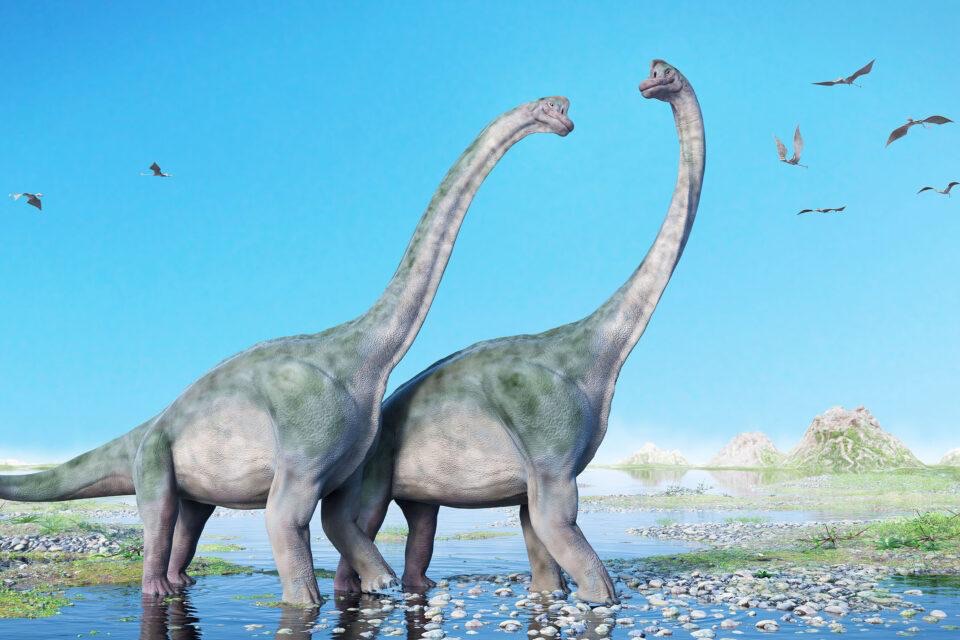

Being retired, I’m sitting here looking out the front window getting weirded out by hummingbirds. Look at ‘em, hovering around the feeder, fighting, stabbing each other—they do, they’re vicious little fuckers around the feeder—and screaming at each other in high pitched strings of hummingbird threats and hysteria. But they’re so cute, you say. Which they are, even I have to give them that. If they were huge they’d be terrifying, but they’re not, they’re dinky, the smallest living dinosaur. And it’s weird to think, if you’re the sort who thinks like this, that they are closer to sauropods than they are to us. That’s right, hummingbirds are more closely related to these huge guys

than they are to us. It’s not that they’re descended from huge sauropods—that would have been some spectacular evolution—but that hummingbird evolution goes back through birds to the last common dinosaur ancestor from which what became sauropods and what became theropods (ranging from tyrannosaurs to the protobird archaeopteryx) which is still a long way from the last common ancestor that we share with dinosaurs. Thus a hummingbird is much closer to those enormous lumbering quadruped brontosauruses than it is to us. And while Deep Time has done some weird shit (us, for instance), you’d be hard pressed to find anything more ridiculous than traces of a mutual ancestor 230,000,000 years or so ago in the skeletons of that tiny hummingbird out there and these whatchamallitosauruses pictured here.

Admittedly, an even closer mutual ancestor can be seen in the skeletons of us and the dimetrodon

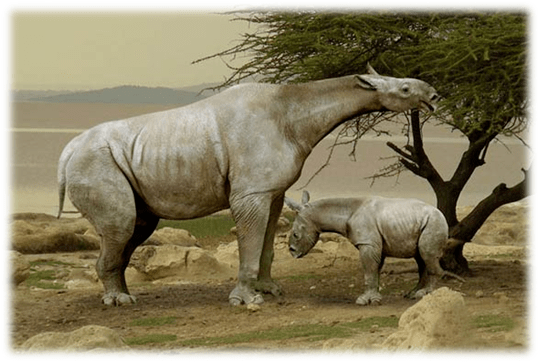

though we didn’t get that groovy sail (which would’ve evolved after the evolutionary paths of the dimetrodon and mammals parted ways), but we both came from the same mutual ancestor way back in the Permian Age, when critters like the dimetrodon (mostly unsailed) were the biggest critters on dry earth, and judging from the number of fossils dug up were as common (if bigger) then as lizards are now. Nearly all were zapped into extinction in the cataclysm at the end of the Permian, though somehow whatever eventually became you, me, your kitty and Baluchitheriums survived.

That’s our connection with the Dimetrodon, at some time deep in the Permian Age what became a dimetrodon and what became mammals were the same critter. Synapsids—you, me, the dimetrodon, but not dinosaurs, we’re all synapsids. (They used to call synapsids the much easier to say mammal-like reptiles.) Those aggro little hummingbirds out there are dinosaurs (really, birds are as dinosaur as we are mammal), which we shared a very distant ancestor with before synapsids even evolved, going way back into the Permian. Back when big amphibians ruled the roost, proto-newts, big scary slimy things the size of Nile crocodiles. Thats how far you gotta go back to see when you and me and those hummingbirds were all tucked into the same genome. So hummers are as much more akin to giant sauropods than to anything remotely like us. Which makes us and that dimetrodon more similar than you’d expect.

And while nowhere near as big as we imagined it when it tumbled out of our package of plastic dinosaurs on Christmas morning (this was a while ago)—I am taller than it was, sail and all—a dimetrodon is still incredibly weird looking. I mean what’s with the sail? Cooling? Warming? Mating? Male gnarliness? In comparison, as tall as I am (six foot five, nearly two meters) I couldn’t even reach the knee of that giant sauropod standing on my tip toes. It’d squish me into the mud on its way to a giant fern tree. I look at all those goddam hummingbirds swarming around the feeder and I think that. The retired life. Now time for my nap.

Dino Luv

It’s National Dinosaur Day and here is a thing I’m not sure I’m glad I saw on Twitter. It’s a pair of sauropods in flagrante delicto about 120 million years ago. The setting is more romantic than realistic, given that these things shoveled down vegetation by the ton and probably didn’t go splashing around the waters off the coast of what is now Texas in what is now the Gulf of Mexico, or perhaps off the coast of Oklahoma in what was a vast shallow sea that bisected North America from north to south and explains all the fossils of giant marine reptiles they dig up in Kansas. Add a few palm trees and huge ferns for a probably more realistic portrait of what two huge dinosaurs looked like fucking, something I had never thought about before but is burned into my memory now. Incidentally, you’ll notice the male came first. Some things never change.

José Antonio Peña, I believe in 1993.

I never metamorphic I didn’t like or if you can’t say something gneiss say nothing at all.

(2017)

Beautiful little piece of reddish rock, layered, I picked up along the side of the road west of the Salton Sea under the assumption it was chunk of petrified wood. Closer examination at home showed that it is more likely a fossilized and mineralized square inch of beach, or perhaps grains of sand laid down in the bed of a slow moving stream, or in an inlet of the long gone sea. Buried and compressed it hardened into sandstone and then was folded into the earth, under millions of tons or rock, and heated by the mantle below (or perhaps the energy displaced by the slow movement of the fault beneath our feet), which transformed the component sediments into something still layered but harder and more crystalline. Gneiss. Not sure where the red came from. Perhaps this was once one of the red sandstones one sees everywhere in the West, littered with dinosaur bones. There was iron everywhere once, it seems to have turned all the sediments red. Perhaps there was more oxygen in the atmosphere then, enough to turn a tree into a torch at the slam of a baseball bat, enough to oxidize all the traces of iron in the sand into a brilliant red. Perhaps. That’s the theory, anyway. Of course, most of California didn’t even exist when that famous red sandstone was laid down. California was still deep down in the mantle, or moving inexorably eastward as ocean floor before slamming into North America. No dinosaurs ever trod the sands that solidified into this stone.

Now I find this little rock here, in the sand, no metamorphic outcroppings let alone mountains for miles. So water dropped it here. Who knows how much weather that took? How many torrential rains and flash floods were required to drop this little rock here at my feet on these archaic flats? It sat there, glittering in the waning sun, surrounded by the sand verbena that clustered in vast herds across the ancient sea floor. They shivered in the dry wind, as if cold, though the temperature was near ninety and the rock was warm to the touch, as if right out of the oven. I picked it up and rolled it about in my hand, thinking of ancient worlds.

Qaxal

(Commenting on Facebook about a photo of a California quail.)

One of my favorite desert birds! And agreed on Qaxal, which looks so lovely spelled out. Alas, it’s probably just about impossible to pronounce for we English speakers, or for just about any speaker of an Indo-European language. From the sounds alone you can feel the thousands of generations that separate the development of the sounds our mouths use to speak English from the sounds a táxliswet (the Chemenuevi word for a Cahuilla person, per Wikipedia) uses to speak the Cahuilla language. Hell, we call the language Cahuilla because we can’t possibly say ʔívil̃uʔat. We call the the tribe Cahuilla because we can’t possibly say ʔívil̃uqaletem. The Spanish called them Cahuilla because the ʔívil̃uʔat word for master sounded something like “cahuilla” to a Spaniard’s ear. That’s right, for master. Amazing the history in a word.

And while we’re not on the subject, though geographically neighbors, the languages the Chemehuevi and Cahuilla spoke are about as far apart from one another as English is from Hindustani. That is both are part of the same language family (as are English and Hindustani) but each gone it’s own way for many thousands of years since they were the same language. Alas, Chemehuevi (which i seem to remember is actually a Mojave word spelled out in Spanish, I don’t know what their own word for their own language was) is now extinct with no living speakers who learned it as children. It survives in academic circles mostly, or in how to pronounce apps (like the one I heard that pronounces “Chemeheuvi” in a beautifully lilting Castilian accent, Spanish music strumming in the background.) Cahuilla is still spoken by a few dozen native speakers but is unlikely to survive them. It’d be nice if either qaxal or kakara, even mispronounced, survived as a name for these desert birds. Neither is likely to. Words from tiny languages tend to disappear with their speakers.

But I digress.

Great post.

Half a trillion Bricks

Today I learned that there are anywhere from 100 million to 500 million sperm cells per human male ejaculation. Or according to another article, from 40 million to 1.2 billion, that is dudes can ejaculate the equivalent of the population of California up to the population of India. I don’t know why some guys have more than others, but most men are somewhere in between those. That’s a lot of little Juniors and Juniorettes. A healthy twenty year old male can easily snuff out half a billion little copies of himself on a boring Friday night. By the time that twenty year old is a fifty year old that might have reached a half trillion copies of himself. Rarely do these thoughts cross a man’s mind at the time, though. Nothing crosses his mind during ejaculation. The frontal lobe goes on autopilot and the thalamus and hypothalamus and various other parts of the brain that pre-date conscious thought take over. It sure feels good, but don’t expect us to write a poem describing it. We can’t even remember it. A hundred million little copies of us just just rushed down our urethras and we’re no more aware of it than a frog is. It’s not until it hits the nerve endings packed into the heads of our dongs that we’re jolted back into consciousness, even speech. Oh god oh god oh god. Like, I said, it’s not poetry, but at least the frontal lobe has sparked into life again. That’s the part of ejaculation we remember. Eloquence comes later, after we’ve washed up and made sure no one was watching us.

I have no idea what happens to the little fellas that never even get ejaculated. How long can a little copy of me wait in there? And what happens to all those me’s then?

I also learned that sperm cells are the tiniest little things, and even a half billion of them only make up about 5% of a dude’s semen, the rest being various fluids, saltiness and flavoring, not to mention stickiness and whatever it is that leaves stains on ceilings. Two thirds of this delicate brew is produced within the scrotum somehow, the other third by the prostate which apparently actually has a purpose. I mean, who knew?

Funny I learned all this at 65, though maybe it’s better that way, so I didn’t suffer guilt complexes afterward, especially since my testicles have been busily producing half a trillion little Brick cells and I’ve failed to reproduce any of them, the poor things. Then again half a trillion Bricks would get pretty annoying. There’s a reason for everything.