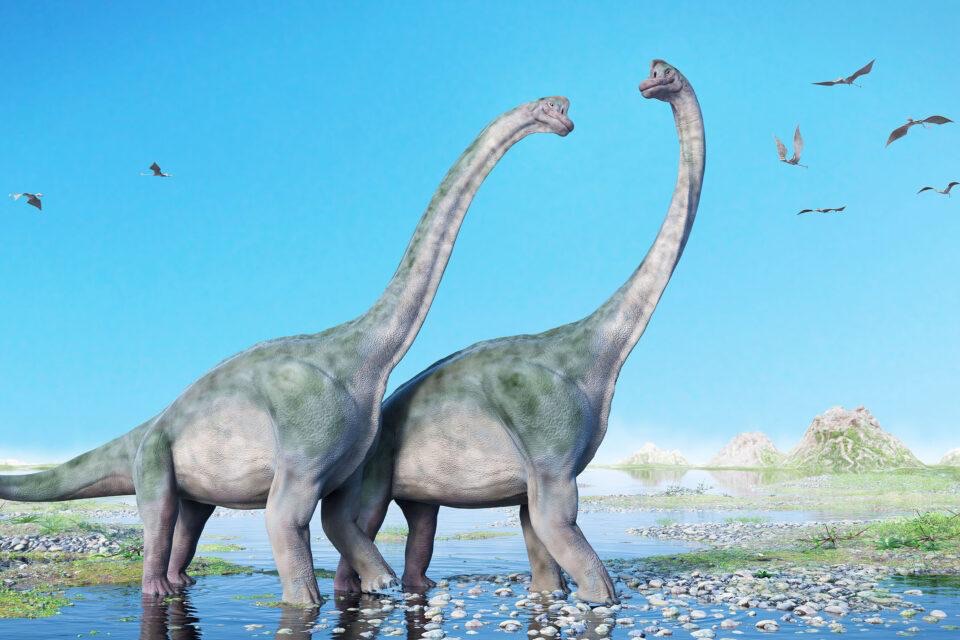

Being retired, I’m sitting here looking out the front window getting weirded out by hummingbirds. Look at ‘em, hovering around the feeder, fighting, stabbing each other—they do, they’re vicious little fuckers around the feeder—and screaming at each other in high pitched strings of hummingbird threats and hysteria. But they’re so cute, you say. Which they are, even I have to give them that. If they were huge they’d be terrifying, but they’re not, they’re dinky, the smallest living dinosaur. And it’s weird to think, if you’re the sort who thinks like this, that they are closer to sauropods than they are to us. That’s right, hummingbirds are more closely related to these huge guys

than they are to us. It’s not that they’re descended from huge sauropods—that would have been some spectacular evolution—but that hummingbird evolution goes back through birds to the last common dinosaur ancestor from which what became sauropods and what became theropods (ranging from tyrannosaurs to the protobird archaeopteryx) which is still a long way from the last common ancestor that we share with dinosaurs. Thus a hummingbird is much closer to those enormous lumbering quadruped brontosauruses than it is to us. And while Deep Time has done some weird shit (us, for instance), you’d be hard pressed to find anything more ridiculous than traces of a mutual ancestor 230,000,000 years or so ago in the skeletons of that tiny hummingbird out there and these whatchamallitosauruses pictured here.

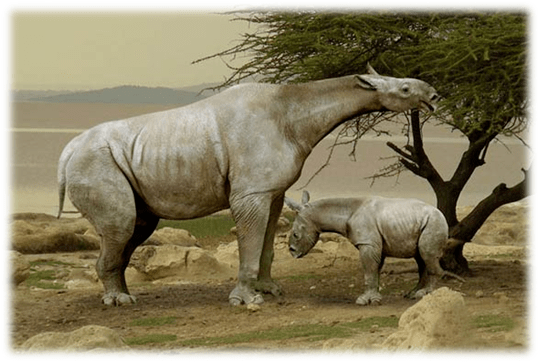

Admittedly, an even closer mutual ancestor can be seen in the skeletons of us and the dimetrodon

though we didn’t get that groovy sail (which would’ve evolved after the evolutionary paths of the dimetrodon and mammals parted ways), but we both came from the same mutual ancestor way back in the Permian Age, when critters like the dimetrodon (mostly unsailed) were the biggest critters on dry earth, and judging from the number of fossils dug up were as common (if bigger) then as lizards are now. Nearly all were zapped into extinction in the cataclysm at the end of the Permian, though somehow whatever eventually became you, me, your kitty and Baluchitheriums survived.

That’s our connection with the Dimetrodon, at some time deep in the Permian Age what became a dimetrodon and what became mammals were the same critter. Synapsids—you, me, the dimetrodon, but not dinosaurs, we’re all synapsids. (They used to call synapsids the much easier to say mammal-like reptiles.) Those aggro little hummingbirds out there are dinosaurs (really, birds are as dinosaur as we are mammal), which we shared a very distant ancestor with before synapsids even evolved, going way back into the Permian. Back when big amphibians ruled the roost, proto-newts, big scary slimy things the size of Nile crocodiles. Thats how far you gotta go back to see when you and me and those hummingbirds were all tucked into the same genome. So hummers are as much more akin to giant sauropods than to anything remotely like us. Which makes us and that dimetrodon more similar than you’d expect.

And while nowhere near as big as we imagined it when it tumbled out of our package of plastic dinosaurs on Christmas morning (this was a while ago)—I am taller than it was, sail and all—a dimetrodon is still incredibly weird looking. I mean what’s with the sail? Cooling? Warming? Mating? Male gnarliness? In comparison, as tall as I am (six foot five, nearly two meters) I couldn’t even reach the knee of that giant sauropod standing on my tip toes. It’d squish me into the mud on its way to a giant fern tree. I look at all those goddam hummingbirds swarming around the feeder and I think that. The retired life. Now time for my nap.